OUR FAMOUS WOMEN.

COMPRISING THE

LIVES AND DEEDS OF AMERICAN WOMEN

WHO HAVE DISTINGUISHED THEMSELVES IN

LITERATURE, SCIENCE, ART, MUSIC, AND THE DRAMA,

OR ARE FAMOUS AS HEROINES, PATRIOTS,

ORATORS, EDUCATORS, PHYSICIANS,

PHILANTHROPISTS, ETC.

WITH

NUMEROUS ANECDOTES, INCIDENTS, AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCES

------

HARTFORD, CONN.:

A. D. WORTHINGTON AND COMPANY.

1884

[c1883]

CHAPTER XXIV.

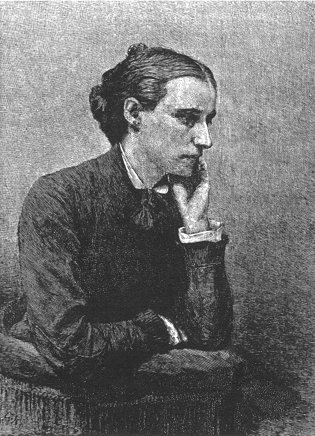

ELIZABETH STUART PHELPS.

BY ELIZABETH T. SPRING.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps' Ancestry—Her Childhood—The Old Home at Andover — Her Story-telling Faculty — Improvising Stories for Her School- mates— Her Education—Pen-portrait of Miss Phelps at Sixteen—Memories of the War—An Unwritten Story— An Incident in Her School-life — " Thimble or Paint-Brush, Which " ? — First Literary Ventures — The Abbott Mission—"The Gates Ajar "—Its Enormous Sale and Helpful Influence—Miss Phelps as a Lecturer—Power Over Her Audiences —Her Summer Home by the Sea—Her Winter Study—Interest in Reform Movements—Personal Work Among the Gloucester Fishermen— The Strength and Sweetness of Her Writings. [pp. 560 - 580]

EMERSON must have been right in saying that we can never get away from our ancestors. He himself might have doubted it if he had watched the rushing currents of life on a frontier, the heaving and swaying tides of prairie seas; hut in New England it is peculiarly true. It is noticeably a fact where generation after generation is subjected to the same influences, where every ray of light, falling unobstructed through the pure air, strikes in hereditary colors. It is like the trailing arbutus, which blossoms pinkest from soil where the pine-tree needles have gathered in accumulating layers through uncounted autumns. One remembers mayflowers, and whatever else is most clearly characteristic of New England, in thinking of Miss Phelps.

She was born August 31, 1844, in Boston, during her father's six years' pastorate in that city. In her fourth May she was removed to Andover, Mass., on her father's taking a professorship in the Theological Seminary there, and Andover

[560]

has been the family home ever since. For her it was only returning to play under the same trees and to breathe the same air that had nourished the genius of her mother and her grandfather.

Her mother, Elizabeth Stuart, was the eldest daughter of Moses Stuart, one of the bright lights of the Seminary in the days when Andover was a main centre of intellectual and theological life in Massachusetts. Professor Stuart was known as a man of moods and variable power, but of exceptional fascination and brilliancy. His daughter Elizabeth inherited the literary gift from him, and though in a style subdued to the tone of the surrounding atmosphere, she wrote several charming stories, largely read at the time. Professor Austin Phelps is known through his widely-circulated book, "The Still Hour." The literary quality was thus present in both parents.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps was the eldest of three children, and the only daughter; and naturally enough as soon as she gave any sign of herself at all the story-telling faculty was indicated in a marked way. She spun amazing yarns for the children she played with, while dolls were still in the ascendant ; and her schoolmates of the time a little farther on talk with vivid interest of the stories she used to improvise for their entertainment.

With this unusual imagination she developed a conscientiousness as definite, and while to bend her will was the most difficult of tasks for those who trained her childhood, her truthfulness could be counted on whatever the storm or stress.

With her surroundings and her nature it was inevitable that her religious development should be precocious. A certain repressed intensity found vent in this direction, and added a deeper tint to what might otherwise have been only the cool spring blossoming of the soul.

She was christened Mary Gray, for an intimate friend of her mother's ; but on her mother's death, which happened when the child was eight years old, the name Elizabeth was given to her instead. The change had a sort of unguessed pathetic

[561]

significance, for in spite of all that the wisdom and tenderness which were left could do life was altered. The mother had singular fitness for watching over the growth of so sensitive and finely organized a child, and her death was no common loss. The little girl had never been exactly gleeful or merry. She had not quite the temperament keyed for joy, and her almost premature thoughtfulness prevented life even then from seeming like a sunlit holiday. So early the hours began to lose their free dancing step and to follow her day with shadowed faces.

It was in many respects fortunate for her, at least since women's colleges were not then more than a dream of the future, that so good a school as that of Mrs. Prof. Edwards existed in Andover. The course was thorough, equal except in Greek to that of the best boys' schools of the day. The curriculum indeed more resembled that of the college than it was usual at that time to find in the educational facilities for women. This girl's bent was towards rhetorical and philosophical studies. The natural sciences, except physiology and astronomy, which seemed to her more clearly to assert their ratson d'etre, did not attract her, nor especially did mathematics.

In spite of De Quincey's assertion that curiosity as to the personal appearance of an author is absurdly irrelevant, it is impossible for those who care for what is written not to care a little even for the face of the person who wrote. There is a photograph taken of Miss Phelps at sixteen, which shows a tall, slender figure, a classically turned bead with a mass of bright brown hair, a sensitive mouth, and an expression of mingled strength and sweetness. There is an air of timidity in the face, but nothing of uncertainty, and amature impression wholly unusual at that age. Looking at this picture one cannot avoid the belief that a skilful teacher, who was strong enough, might have guided her into almost any fields as her mind developed; but at nineteen she left school.

White flowers and martial music in May, with dim traditions of battle and march are chiefly what the civil war means

[562]

ELIZABETH STUART PHELPS

[563]

[564 blank]

now to the young girls who live in the day that followed that darkness; but there does not live the tragic bard to say what it meant to those whom its midnight overtook. The Greek Simonides tells us of the heroes — " Their country's quenchless glory," who " won for themselves the dusky shroud of death " and " live by that same death and its echoing story; " yet freedom may owe as much to the limitations, the interruptions, the conscious and unconscious sacrifices of the daughters " who give up more than sons."

It was Dr. Holmes who prophesied at the close of the war that the generation which had passed through the terrible strain would have shorter lives, — that many years had been compressed into that brief and fiery epoch. However this prophecy may prove, it is certain that the unwritten story of the period, the story with its sequel, would tell of more battles of the wilderness and more prisons than all the histories.

Many, like Miss Phelps, devoted themselves at the close of the war to philanthropic work. For a few months after leaving school she threw all her energy into mission work in Abbott Village, a little factory settlement a mile or two from her home; but the forces in her, for which this gave no scope, soon began to assert themselves, and in the spring of 1863 she sent a war story, called "A Sacrifice Consumed," to " Harper's Magazine." The editor returned her a generous check for it, with the request that she should write for them again. It was appreciation for which she has always been grateful, coming as it did when she was uncertain of her own power and peculiarly in need of encouragement. She has been a frequent contributor to that magazine from then till now. " Harper's never refused a story of mine in all my life," she says, " with one single exception — that not when I was a beginner. To this uniform encouragement I attribute more than to any other one thing what literary success I afterwards had."

" The Tenth of January " appeared in the " Atlantic " later, and gained literary recognition, besides exciting profound

[565]

interest. It was a story of the burning of the Pemberton Mills at Lawrence, a realistic picture, quite as vivid as any the author has made since.

She had written a little at intervals before; the first thing she printed being a story in the " Youth's Companion." She was then thirteen.

The artist element was strong in her nature. She had extreme sensibility to color, and no little skill with brush and pencil. While she was still walking in the bright mist of her young girlhood, seeing the future through eager eyes, though dimly, the artist life was one of her dearest dreams.

With this went a certain distaste for the usual feminine employments, arising from a vague opinion that to sew meant to do little else, and from a positive rebellion against being cramped away from her full native bent. It was in a mood of this sort she one day held up to a school friend a thimble in one hand and a paint-brush in the other, saying: "It is a choice between the two."

As might be guessed, no poet was dearer to her in those days than Mrs. Browning, and nothing kindled her enthusiasm more than reminders of women who had risen above conventional low tides and dared to be themselves.

Gradually the play of various forces conveyed her possibilities mainly into the literary channel, though her sympathy with suffering, quickened by the experiences which gave color to the rest of her life — blended with her native earnestness, made certain that active philanthropy in some form would go side by side with the other.

When the first effort to throw all life into the mission work at Abbott Village had passed, and after the two stories had spoken out like the first notes of a bird after a storm — at twenty the plan of " The Gates Ajar " began to form itself in her mind. She was busy in writing this book for two years. It lay for two years in the publisher's hands, and came out in 1868. Although the first, it is the best known of all her books. It reached in this country a circulation of about one hundred thousand copies, and has had a very large English sale.

[566]

It has been reprinted in Scotland, and translated into German, French, Dutch, and Italian. Most of the successive books by the same hand have been thus reprinted and translated.

A friend of Miss Phelps, travelling a few years ago, was introduced to an officer of rank in the Prussian court, and Miss Phelps' name being mentioned, he said, " Ah, that book, ' The Gates Ajar; ' I understand it has made more Christians than all the preachers."

Like most books that have had positive and helpful influence, it originated in honest questioning and honest search. There had long brooded over the church of America and England, the shadow of prescribed silence on everything relating to the future life. Speculation had been frowned upon, as baseless and irreverent, hope had been forbidden to think, and the " better land " lay far off in a frozen mist of negative and unreal glory.

One could turn to Dante's "Paradise," sombre and massive as Gothic architecture, or mediaeval theology, but the trees by his river of life have little for human nature's daily food. There is something so vague, remote, impersonal in the atmosphere that we do not wonder Ary Schaeffer painted no rapture in the reunion of Dante with his lost Beatrice.

At the opposite extreme there has been Swedenborg — , mild as Dante was stern, full of spiritual insight and genius for expanding the tiny tent of certain testimony into a canopy large enough to cover the widest yearnings of human love and aspiration. But Swedenborg had gathered a sect about him. His teachings as to the coming existence were so overlaid, too, with other speculations that they were hardly available for the every-day comfort of sad and wistful souls who need something appreciable and readily grasped. Eyes tired with weeping for lost friends cannot search through tedious volumes for words of suggestion and hope. Surely it was time for a woman's gentle word — a sweet fireside word — as far withdrawn from Italian terrors as it was from Swedish dreams.

[567]

"The Gates Ajar" was at first doubtfully received by many. The graver part of the community were forced to read but inclined to frown. Pianos and gingerbread seemed startling and trivial contrasted with seas of glass and cherubim and seraphim, hitherto made so prominent as features of the home of human beings set free from earthly hindrance. Others eagerly welcomed the new suggestions, for under the teaching that had prevailed, owing to a crude habit of biblical interpretations, so dim, monotonous, and narrow had been the representations of heaven, that to most ardent souls or active minds annihilation seemed hardly less dreary. The framework of the book was so simple and the method of treating the subject so fresh that very many failed to detect at first that its logic might not be less conclusive because it was not ponderous. They forgot that it is a very old tradition which makes the angel come at dawn, in the cheerful morning twilight, to guide the souls of the good to paradise, and that twilight fancies are the sober truth of twilight, as mathematics may be the truth of noon. In story form, and by suggestion, the book attempts to show that the heavenly life must provide for the satisfaction of the whole nature, as well as for the technically religious side, the one department which seeks God directly in personal affection and .worship. On reflection, those who had most rigidly confined their hopes of future to white robes and singing, discovered that even —

" The stainless years

That breathed beneath the Syrian blue "

were filled with much besides direct prayer or praise to the heavenly Father, so that imperfection could not attach to this idea of roundness ; and gradually it befell that many who came to scoff remained to be comforted. The book was practically a new gospel. Indeed, "The Gates Ajar" did more than expand into appreciable size and surface the neglected germs of truth relating to the unseen world. It marked in a gentle, unaccented way, but it marked the beginning of a change whose end we can hardly foretell.

[568]

The world has long enough seen in every gallery the infant Christ in the arms of a woman; but it has not always seen that through womanhood it is to receive some essential revelation of Christianity. It has understood only the surface meaning of Madonnas, and has tired of that; but at last what art has dimly been foretelling is beginning to be actual. Whether in the cap and 'kerchief of Sister Dora and Sister Augustine, or with the red-cross badge of Clara Barton, or wearing the unmarked dress of those who feed the hungry and teach the ignorant near and far off, new Madonnas are revealing something more beautiful than beauty, and holier than any image in shrine,

Miss Phelps now devoted herself to short stories, which were collected under the title, " Men, Women, and Ghosts." So far as vivacity, proportion, and firmness of touch are concerned, they contain some of her best work. The "Tenth of January" is included in this collection. There is a study in spiritualistic science called " The Day of My Death " which ends more happily than most of her tales, and goes far to disprove what some critic asserted about her " inevitable tug at the heart-strings."

Her definite moral purpose became distinct so early in her literary career. As Millet would paint peasants no other than they were, whatever Delaroche might say, she would have sorrowful things show their sadness that they might be helped, and wrong things their evil that they might be righted.

In the autumn of 1877 a venture full of interest absorbed Miss Phelps' thought and strength; the delivery of a course of lectures on "Representative Modern Fiction" before the Boston University. It was the first thing of the sort ever attempted by a woman in this part of the world, and in the minds of those most interested there was the air of a renaissance in the undertaking.

The intense vividness with which the ideal presented itself to her, combined with a sensitive timidity which amounted to terror, robbed her of sleep for weeks before the course began,

[569]

and prostrated her with illness after it closed; yet while constantly under the physician's care she met each engagement bravely, and left only one regret in the minds of her friends, that her health had not allowed her to speak in a much larger hall. The lectures have never been published, so that personal impressions are all that we have.

Her power over the audience is said to have been remarkable. While her voice in conversation is singularly low and sweet, some peculiar penetrative quality made it distinct without the slightest effort for the listener in every part of a large hall. The audience was of students of both sexes and different ages, from various departments of the University. At the close of every lecture," says one who was present, " they would gather round her, and it seemed as if they would devour her, following her as far as possible when she went away." Something in her face seemed to ask more for love than praise. To them it seemed as if a new and gentler Hypatia had come to speak a sweeter sort of wisdom. Mr. Whittier, who on another occasion heard the lectures, says of them: " They were admirable in manner and matter. I have never heard a woman speak with such magnetic power."

In treating modern fiction she concentrated her analysis on George Eliot as representative. President Warren of the University says, " The genius of George Eliot has never been analyzed with superior, if with equal subtility of sympathy and clearness of discrimination."

So serious were the physical penalties for that use of her undoubted power that she has been obliged to abandon public speaking; though she made several experiments after this both in hall and parlor reading — in every other respect, she says " among the most delightful experiences of her life." An interesting account is furnished of her reading one of her stories for a charity in a private parlor in Boston. It was an audience composed of fashionable ladies, and the story was a very simple one, but before she finished her reading it was said there was not a dry eye in the room—a kind of compelling sweetness drew their hearts towards her and pity.

[570]

In the same autumn of her work at the Boston University, "The Story of Avis" came out. The public feel something in it like the deepening of a singer's voice, as life teaches its lessons, a strength born of patience, and a pathos that no unreflecting outcry can hold.

The world seems to be divided into three classes: those who do not know there is a sphinx; those who do, and will not look at it; and those who, seeing it, are willing to make some sort of effort to unlock the silent lips, to read the riddle of the past into the prophecy of the future.

For the first, Avis must be as if it had not been written, while to the multitude of those who do not want to be made uncomfortable by thinking of hard things it will not be exactly welcome. There must be many who are willing to think even of perplexities, for many have prized Avis, and have called it Miss Phelps' best work. It is said that Longfellow kept it lying on his table, and re-read it often with sympathetic appreciation.

Avis is a woman such as one has seen — strong, gentle, true, with a genius for painting. There is no happier stroke in the book than that which makes her not simply in love with her art and ambitious to excel, but gravely conscious of responsibility for the use of her talent. Her course looks simple and direct till Philip Ostrander, and with him love and the question of marriage, confronts her, sweeping into her life as the tide into the harbor. She resists love, but when her denied lover comes back wounded from the war, the woman asserts herself above the artist. "The deep maternal yearning over suffering, more elemental in woman than the yearning of maiden or of wife," conquers where his pleading had failed, and by exquisite gradations, possible only to a woman of equal fineness and exceptional individuality, she yields and becomes his wife.

The very idealizing nature that made her able to paint sphinxes, made her mistake in Philip Ostrander subtlety of appreciation, sympathy, and the genius of adaptation for something deeper. It is made clear that a man less refined

[571]

and less sensitive could not have won her, and no less evident that refinement often binds the artist-eye to weakness, and that the quicksilver temperament fascinates where it cannot hold.

Large, sweet, genuine, like Dorothea, Avis does the only thing possible to such a woman, buries her short-lived ideal and takes Philip into the same pitying tenderness which broods over her children; endures and strives and loves as nobly as any other could who was not conscious of unpainted pictures or any missed vocation.

Recent American fiction has given us various types of women. We have Marcia in " A Modern Instance," weak, passionate, unreasonable Marcia, swept under by the first swell in the domestic flood. Mr. James has drawn Isabel Archer best of all the women he has tried, and he has made her almost lovable, or would if he knew about women's souls. Despair and flight are her resort when disenchantment is complete, and pain grows heavy. He makes us sympathize with her; but she seems vague, shadowy, and weak beside the nobler figure of Avis. It is impossible to imagine poor Marcia being anything else than petty; unfit to reform Bartley and unworthy of the better man's devotion ; and with all that is genuine and earnest in Isabel Archer, it is difficult to think of her in Avis' place, bending with conscientious good sense to conquer the homely details of housekeeping, or substitute with so silent a gentleness the maternal for the wifely feeling towards the weaker nature which failed her.

There are touches in one of the closing chapters of "Avis" which remind us for delicate, fervent purity of faith and insight of the sayings of Lamartine's "Stone-Cutter." In the farewell Philip and Avis whisper to each other when he lies dying in the Florida forest, we can almost hear Claude saying, " Life is so small a thing, it is not worth stopping to weep over." Indeed some of the most exquisite qualities of Miss Phelps appear in " Avis " more clearly than in any other book. Only a pure and exalted soul could have

[572]

conceived it; and only a genuine artist could have given it its cast.

Six years ago Miss Phelps built a little cottage for a summer home on the rocks of Eastern Point, at one side of Gloucester harbor. There is hardly a more rugged spot on Cape Ann, or one more lacking in the lovely surroundings those who know her best would have chosen as fit and natural for her. But one forgets all but the picturesqueness of the shore in looking out on the harbor with the quaint old town of Gloucester at its head. The harbor is one of the finest on the Atlantic coast, and there, from June to November, the infinite language of the sea repeats to her its story of beauty and mystery.

All coasts are lonely in some moods of water and sky, but Gloucester harbor is wide enough to shelter a fleet, and there are always sails standing in or out to sea, playing hide-and-go-seek with the mist, and taking the light and shadow at every turn in new and exquisite tones. A mile away, across the sheltering rim of land, the narrow strip that curves around the harbor's mouth, the surf breaks on the rocks, or rolls in on the sandy shore of the coves that follow one an- other out to the extreme point of the cape.

Miss Phelps still makes Andover her winter home. Her present winter study is in the summer-house of her father's garden, whose windows look out on a lovely grove, and behind, towards the west, across to the brows of Wachuset; but her summers, which begin early and end late, find her on the Gloucester rocks.

The first years of her life here she used to row in her little dory quite across the harbor, an exercise of which she was very fond. Lack of strength has compelled her to relinquish it of late, and the dory lies idly by the rocks, except when she occasionally steps into it for a few strokes of the oars out into the sunset. What the sea has told her she has meanwhile given to us in different forms. In her volume of " Poetic Studies," most of the rhymes are tinted with the opal and beryl of the waves; and we feel through them the

[573]

ebb and flow of tides. Several of her songs have been set to music — words and notes blending in a kind of twilight aspiration—an unaccented appeal.

" On the Bridge of Sighs " is an original and apt analogue, fit to be written under that picture of sun opposite to shadow which every traveller brings home from Venice: —

" 0 palace of the rose — sweet sin,

How safe the heart that does not enter in —

0 blessed prison wall! how true

The freedom of the soul that chooseth you."

" What the Shore says to the Sea " and " What the Sea says to the Shore," and the last poem in the collection, " All the Rivers," are perhaps the best translations she has made of that speech she has heard where there is no voice nor language. " 0 Love ! " the shore says at ebb-tide to the sea: —

" Steal Up and say, — is there below, above;

In height or depth, or choice or unison

Of woes, a woe like mine,

To lie so near to thine,

And yet forever and forever to lie still?"

And at flood-tide the sea answers—

" Till thou and I were riven apart,

Never was it known by any one

That storms could tear an ocean's heart.

When unheard orders bid me go

Obedient to an unknown Will,

The pain of pains selects me, so

That I must go and thou lie still !

" All the rivers is a word of peace —

All the rivers run into the sea,

Why the passion of a river ?

The striving of a soul ?

Calm the eternal waters roll

Upon the eternal shore —

At last whatever

Seeks it — finds the sea."

[574]

Yet the poetry of the ocean has not made her deaf to its tragic prose.

" Sealed Orders," a collection of short stories published not long after " Avis," has one or two pictures, not easily forgotten, of winter storms in the ice-bound harbor, the cruel struggles of the fishermen for scanty bread, and the more cruel watching and waiting at home "for those who will never come back to the town."

Critics have called "The Lady of Shalott," one of the sketches in this collection, the best American short story. It shows, like the rest, the subjection of the aesthetical to the ethical, the artistic to the sympathetic in her nature; but here as elsewhere the unused brush and palette assert themselves in spite of denial. What she sees inevitably shapes itself into a picture, and what she might have done had she chosen to paint with her pen all such pictures as would charm, we can only guess. If she had, we should have known less about the lonely little dressmaker in "No. Thirteen," or the two brothers in "Cloth of Gold," trying to get to Florida with far too little money, and walking where they could not ride, with Dan, between his coughs, insisting that he felt very strong, and that it did not hurt him at all. We should not have cried over the "Lady of Shalott," and tenement houses with death in the cellar, and nankeen vests at sixteen and a quarter cents a dozen, and the blessed "Flower Mission," and we should not have felt—as whoever reads such tales will—that something must be done to help those who cannot help themselves.

It adds always to the force of one of these lessons in philanthropy or reform to know that the teacher is herself in earnest, and " recks the rede " she gives.

That Miss Phelps' roses have all true stems that will not wither we can tell by tracing her life. She was trying to save the tempted in the Abbott mission when she wrote " Hedged In "; and the evils of factory life depicted in " A Silent Partner" she learned by personal work for factory girls; and from her loyalty to the purer, larger, and freer

[575]

womanhood that all dream of and wait for she has never swerved. Hers was not the only sensitive intuition that foresaw, when slavery and the war rolled away together in fire and smoke, that the right development of women would be the next great question for America.

It is said that Warwick Castle in England is so arranged that the visitor who looks through the outside keyhole looks at the same time through those of the thirty or forty apartments that lie beyond; and so in this matter of making the higher, larger womanhood a fact, one cannot begin without finding that woman is so entangled in the heart of things that all must be righted if she is.

The first glance told that her physique must be improved. As early as 1869 Miss Phelps was invited to give an address before the New England Woman's Club of Boston on healthful dress for women. The time was ripe, and the suggestions of the speaker's practical common sense were instantly adopted. Rooms were opened for the manufacture and sale of improved garments; competition followed, and the dress reform, so widespread and increasingly influential now, is said to have grown from this. Miss Phelps' address, somewhat enlarged, was published, with the title, "What to Wear," and she herself adopted and has always adhered to the system proposed, abjuring trains, and excessive trimmings, and tight waists, and modifying her theory only in such non-essential points as experience and good taste dictated. It seems hardly possible now that, at the time she took this course, a lady could not walk the length of a hotel drawing-room in a short dress without an embarrassing sense of singularity, so universal was the absurdity of sweeping skirts everywhere and on all occasions.

No sooner was Miss Phelps' summer home planted on the Gloucester shore than the temperance movement appealed to her as vitally connected with the object of her lasting enthusiasm. She saw how intemperance on Eastern Point added a cruel weight to the hard lot of fishermen's families, and through her efforts a Reform Club of sixty-five members was

[576]

sustained there. A club-room had been otherwise secured; it was brightened with pictures and music; addresses were delivered and sermons preached to the men; but her personal work was of a deeper and more wearing sort. She made herself the friend of each one. They came to her house with their hopes and despair, their temptations and troubles. As might have been feared, this nervous strain of sympathy and anxiety, in connection with her literary work, was an overtax, and four years ago her strength gave way, forcing her to drop the care. From this nearly fatal break she has not yet physically recovered.

Since 1879 we have had two books from her, both originally published as serials in the "Atlantic Monthly," and aside from these, some noticeable magazine articles of a semi-theologic cast in the " Atlantic " and " North American Review." The one in the "Atlantic," entitled, "Is God Good?" called out an amount of discussion surprising when one considers how long ago it was that mild old Dr. Paley ventured to speak of "The goodness of God as proved from nature."

Her argument is that immortality is necessary to justify the earthly life, and is not more than a deduction from the gently suggested premise no one quarrels with from the lips of St. Pierre, " If life be a punishment, we ought to wish for its end; if it is a trial, we may ask that it may be short."

"Friends—a Duet," has been variously criticised,—a certain intensity of adjectives and repetition of favorite words, which some objected to in "Avis," giving fresh offence to reviewers in this book.

It may be worth while to mention that Miss Phelps never reads any reviews or notices of her own books, thinking perhaps the nervous force required for this better expended in persistent effort to speak out in her own way the things life has taught her. She has certainly a sufficiently illustrious precedent for her habit in this respect, since it is said that George Eliot herself had the same practice.

[577]

"Friends " is a study of a new phase of the same old mystery. A delicate, difficult phase, but pressing as the question how to manage steam, fire, or electricity. The voices in the " Duet " are better harmonized than were those of Philip and Avis. In the rise and fall of gentle and sweet music, the question and answer of a simple natural progress, there is a wistful search for knowledge whether between men and women there cannot be, as in other times there has been, friendship without love and marriage; a May of tenderness and mutual help that does not " glide outward into June " — affection without passion. It ends as some songs end, with a strain, more an appeal than a conclusion, a little sad— as if we heard again Schiller say "Never can the there be here."

There is something about it all that makes one think of the wild pink roses with which the downs of Eastern Point are covered in the summer, and with which Miss Phelps' house is always filled. There is a delicate mirth, a sweet, refined, protected atmosphere in it, yet though more bidden than sometimes, we find on it the same sign of the cross as before. Still, as Millet's seashore "Storm" or "Angelus " would do more than make us note the massing of clouds and the rage of the water, or the wide peace of the fields at the hour of evenning prayer; as he is not content till we ask, " What can be done for the bowed and laden creatures who are the centre of the scene? "—so, in "Friends," we are compelled to do more than watch the rose-red glow that slowly and faintly kindles in the gray sky that overhangs the principal figures. The story leaves us as the "Scarlet Letter" does, looking toward the time " when the whole relation of men and women shall be established on a surer ground of mutual happiness."

" Dr. Zay," Miss Phelps' last story, is pitched in the major key. It has been a surprise to the public, so long used to listen for the minor in every strain of hers. There is morning in this picture. " Avis " was sad because there was in it only the wish for the day. "Dr. Zay" stands out clearly in the light of dawn.

[578]

Miss Phelps has felt the change of atmosphere within the five years, since she said at the close of "Avis," " Horizons with which her own youth was unacquainted beckoned before her; the hills looked at her with a foreign face; the wind told her that which she had not heard; in the air, strange melodies rang out." One of these melodies is caught and rendered for us here. It is a glimpse of—

" Man and woman

Solving the riddle old."

It seemed to have occurred to none but Mr. Howells before (unless we except Charles Reade), that there is suddenly a new type of woman for the novelist to deal with, and " Dr. Zay " was already half-written when " Dr. Breen's Practice " appeared in the " Atlantic." Mr. Howells' woman physician has not however " the scientific mind." She was, after all, only the old sort of woman he knows so well, masquerading with a medicine-case. Dr. Zay means it all and does it too.

Without a stretch or twist, very simply and naturally, though we must believe not without intention, the ordinary conditions are precisely reversed. It is her chance patient, Waldo Yorke, who is passive, unoccupied, "a beggar for a kind word." It is she who is preoccupied, active, happy in a full and satisfied life. That marriage is not to be entered into unadvisedly in the new order of things is made sufficiently plain by her long hesitation—hesitation under his wooing, and by the high-mindedness with which she refuses to let him err through any glamour of gratitude, loneliness, or circumstance. Not till his choice is tested by change and absence, and hers by persistent work, does she yield, like other women who cannot prescribe carbo vegetabilis or set broken arms.

The book is full of smiles and west wind and hope, instinct with prophecy, already beginning to turn to facts. It is all natural and direct, quite free from morbid or one-sided views. Whoever reads it is apt to be carried on by Miss Phelps' theories in spite of himself, since he finds such a new

[579]

kind of woman as Dr. Zay proves to be, a very charming and inspiring sort of creature. He inclines to agree with Mrs. Isaiah Butterwell, that there might be worse things than "having a woman like Doctor to turn to, sharin' the biggest cares and joys a man has got, not leanin' like a water-soaked log against him when he feels slim as a pussy-willow himself, poor fellow, but claspin' hands as steady as a statue to help him on."

The vigor and sparkle of " Dr. Zay " make us believe we have better things yet to expect from Miss Phelps in spite of the baffling, almost crushing, hindrance of ill-health. That bar once removed, what fine insights, what holy inspirations, what pictures of the droll as well as the pathetic side of things, may we not anticipate from a nature so strong and beautiful, gifted with so rare a genius of expression?

If fate should deny it, her life and work, as they stand, are among our choicest treasures. Her high-minded constancy to her difficult ideals adds to her personal charm the haunting fragrance of a purely spiritual force, and wherever her words fall, unfading flowers spring up.

In her, and in her writings, force and sweetness so blend that we cannot tell whether it is the beautiful that draws us, or the good and the true that stimulate and content us. If the flower is a lily, it is an Easter lily, with comfort and ministry in its grace, an ethereal and immortal meaning folded in its rare, white petals.

[580]

Back to main page